What’s in a Name? Bruce Li on ‘Patternways’

24.02.2023

Emblematic of ownership, status, aestheticism and cultural significance, patterns are ornamentations that have long adorned the surfaces of our textiles, pottery, architecture and more. From patterns of regular geometry, ornate florals and flourishes, to visually striking and contrastive colour blocks and even other non-figurative forms, patterns can be found all around us. Let’s dig deeper beneath pattern’s decorative surface through the display ‘Patternways: Visualising Hong Kong in Transition’ at The D. H. Chen Foundation Gallery.

The special display presents 4 significant patterns of Hong Kong. Each pattern is examined as a designed product and the way it has circulated worldwide. The following article is based on an interview with Bruce Li, the curator of the display, in November 2022.

Can you talk us through the title of the display: ‘Patternways: Visualising Hong Kong in Transition’?

The title ‘Patternways’ is a composite, made-up word. Aside from a title that’s punchy and easy to understand right away, I also wanted to give a direction to the exhibition – a feeling of things going to places. Because that’s what patterns do, they circulate. Another element of the exhibition is tracing the historical context of a pattern design. ‘Ways’ encapsulate that idea of paths, movement, tracings.

Fabrics with auspicious Chinese motifs

Fabrics with auspicious Chinese motifs

And finally, ‘Patternways’ is also a play on the textile terminology ‘colourways’, which are the various colour combinations you can have for the same design. This new coinage implies variety, variations. And that’s what patterns are. There’s a variety of aesthetics, of ways that they repeat, a variety of applications. And likewise in the exhibition, there’s a good variety of 4 case studies of these patterns. In short, ‘Patternways’ is punchy, suggestive of directions and implies variety.

To me, patterns is a way to read and look into Hong Kong. That’s where the ‘visualising’ comes into play. When you try to define patterns, you’ll realise it’s more complicated than you think it is. Is it just a repeating element? If so, how does it repeat? How does it function in textile, or on paper?

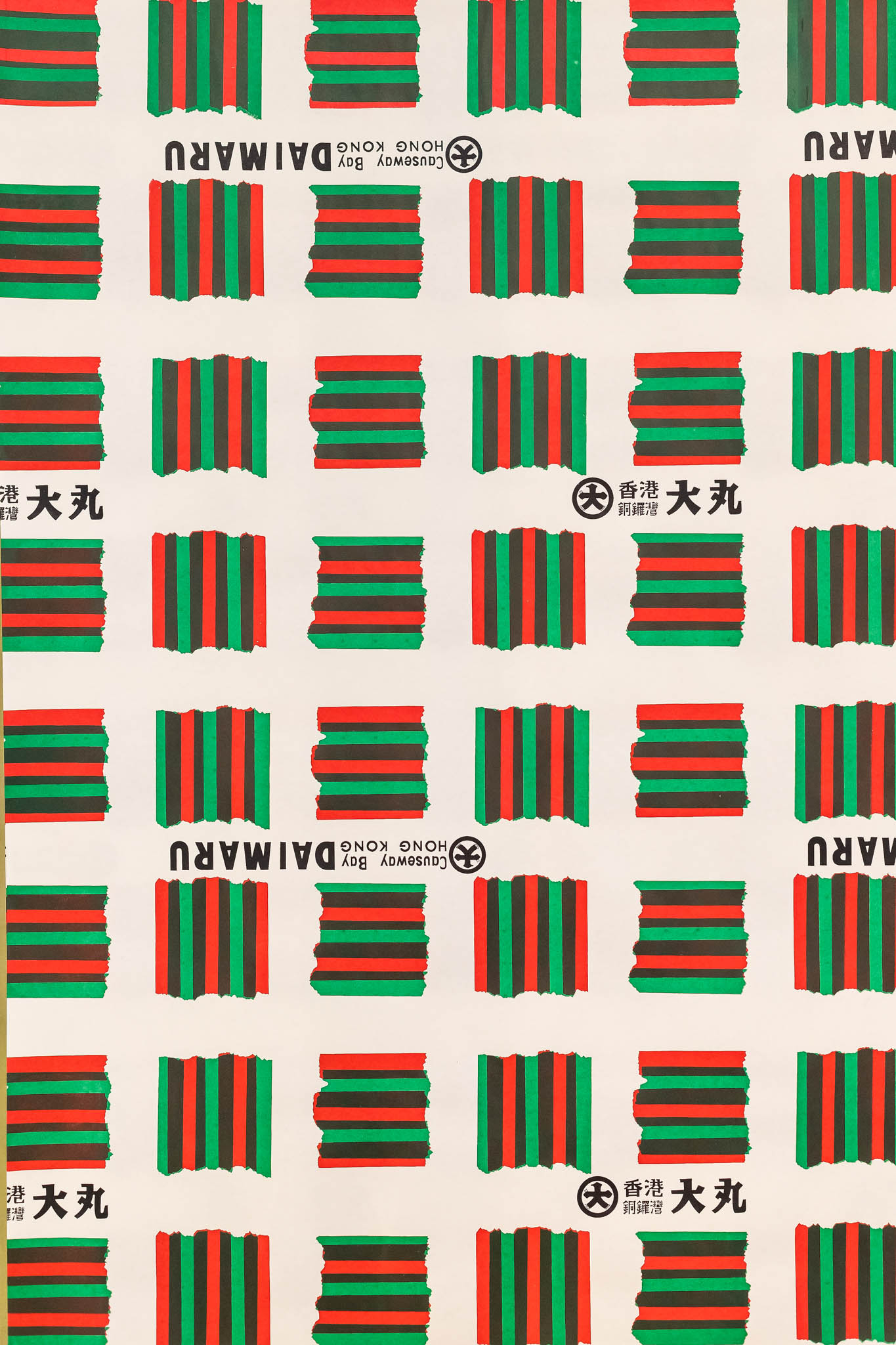

Replica of Hong Kong Daimaru Department Store wrapping paper

Replica of Hong Kong Daimaru Department Store wrapping paper

There are many ways to look into patterns, but there’s a specific lens in this display, and it’s through Hong Kong and through Hong Kong being adaptable to, and taking advantage of change. And this is what this exhibition is about.

Exhibition drawer with Lane Crawford and Daimaru branded materials

Exhibition drawer with Lane Crawford and Daimaru branded materials

So what are patterns exactly?

Formally speaking, pattern is an image of repeating elements. These elements could be repeated as a mirror image, or more complex as in a half brick drop (where the image repeats across horizontally but half a repeat-size down vertically, like a paved brick road). There are many different ways a pattern could repeat, and that’s the way most people think of patterns: in terms of plaid or polka dot, etc.

Digitally printed pattern fabrics by Hong Kong’s China Dyeing Holdings

Digitally printed pattern fabrics by Hong Kong’s China Dyeing Holdings

Then there’s also a more abstract pattern, which is how things behave: how things happen, how they unfold, and a prediction of things. And in the research process of this exhibition, I discovered that there was a pattern in which Hong Kong seemed to be very good at adapting to market conditions or economic circumstances, even at challenging times, resulting in interesting designs. There was a pattern to the behaviour of design that arose.

There’s the interesting action of mapping – of putting things into order, structure and form. And that idea of mapping interestingly circles back to how patterns have moved through different geographical locations in relation to Hong Kong.

Yes, I think patterns are a way to give form to an idea. Through this display, if we were to re-centre our attention to this thing that we often overlook, it does reveal ideas of circulation, movement, and things that are otherwise more shapeless. I think patterns are a good way to do that.

So why have you chosen patterns to be the focus of your display?

Patterns are a very important visual language to me. I come from a background in textiles, specifically textile design. Having been trained in designing a pattern, you come to realise how difficult it is to make a ‘successful’ pattern: one that is supposedly balanced, that doesn’t ‘track’ or stand out when you look at it from afar, but is harmonious. It is with that training and practice that I cultivated an interest in and an appreciation of a good pattern.

In art school, I was taught to meld design with fine art, and to look at patterns from a fine art perspective: What does it mean to make a pattern instead of a painting? Patterns are typically associated with adornment, and regarded as frivolous. Compare patterns with the ‘authority’ of a painting or a singular image. You might believe and trust the contents of a photograph or a painting more than a pattern.

And likewise, the craft of textiles – patterns being closely associated with textiles – is also something that is easily dismissed. There’s a whole discourse around textiles being a craft, being women’s work, being underappreciated. So that’s how I see patterns: It’s easily forgotten, but there’s great subversive power to it, and rewarding when you regard it with the same reverence or attention as you would a painting or a photograph.

Red silk coverlet and other silk products

Red silk coverlet and other silk products

But the benefit of being overlooked is that it is a lot more flexible and honest, in my opinion. It might not go through the same level of scrutiny or discussion – on its political correctness, its validity, legitimacy – as a singular image or a painting. They often reflect the taste of its users.

Cultures also often borrow each other’s patterns. It bridges and crosses into different places and cultures easily without much scrutiny. It’s inherently very honest to that moment in time. It’s a visual language that is very contextual to a circumstance. There’s an immediacy and honesty that the baggage of a painting or a photograph might not be able to afford.

Shared Routes wax print designed by Rachel Wood, printed by Akosombo Industrial Company Limited

Shared Routes wax print designed by Rachel Wood, printed by Akosombo Industrial Company Limited

One example would be the wax prints from our exhibition display. Some people call it African wax print, with a great variety like Ankara, kitenge, and many more. But it is that quintessential pattern or aesthetic that is adaptable and cross-cultural. It’s associated with Africa, but it has global origins. And even among designs worn by the African community and the diaspora you can still find elements borrowed from other cultures.

Wax print process

Wax print process

In the research process of ‘Patternways’, we’ve also seen design studios of wax print that has a library of books that their designers could draw from. And often these books would be about the Japanese Edo period, Chinese Tang Dynasty motifs, Indonesian batik. And these designers would borrow them in their studio in England and put them together into a wax print that is then sold or made in, say, Ghana. Which brings us back to the idea of circulation.

In recent decades, discussion surrounding wax print with regard to identity politics and its origins has made it even more interesting, and dense, and rich. Of the 4 case studies I present in ‘Patternways’, wax print is probably the one that deserved a full-on exhibition. Through ‘Patternways’, what I could add to the discourse of wax print however, with the help of some very generous supporters and companies, is the involvement of Hong Kong and the participation of East Asia in this industry.

Stay tuned for more about ‘Patternways: Visualising Hong Kong in Transition’.‘Patternways’ is on view at The D. H. Chen Foundation Gallery at CHAT until late 2023.