Thoughts on Blue: Kaji Kakuo

29.11.2022

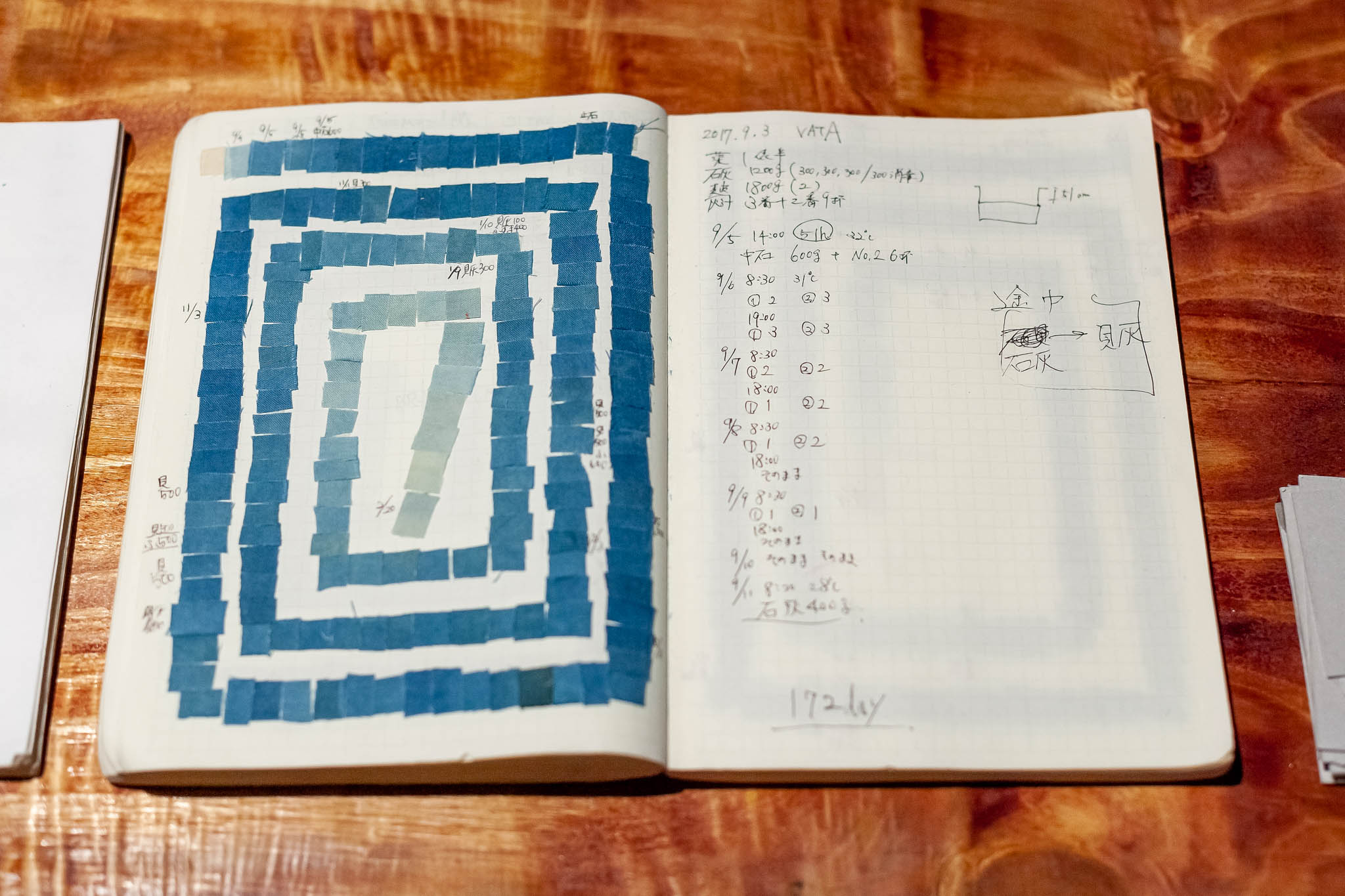

Kaji Kakuo, a founding member of Japanese indigo dye collective BUAISOU, shares his thoughts on indigo and his journey in the craft of indigo dye.

For some, a passion for craft can be so ingrained into every fibre of their being that it leaves indelible traces, thumb prints and stains, in every aspect of their lives.

On the occasion of its Winter Programme 2022, CHAT speaks to curators and craftspeople involved in Absolute Blue: BUAISOU Works with Japanese Natural Indigo, to explore the fascination with the colour, medium and craft of indigo.

What does blue mean to you? How does blue make you feel?

KK: When I was younger, there used to be that assumption that all boys must like the colour blue. So blue never held any charm for me, I didn’t like it as a colour that much.

I started enjoying making things with my hands, and came across botanical dyeing. And realising that it is something you can do in your home, I became intrigued by it. After I started this practice, I realised much of botanical dyeing involves a sort of extraction from the plant. Boiling and then dyeing with the extract. But indigo dyeing is entirely different. I was deeply drawn to this unique alternative method of creating blue, and so indigo has deeply fascinated me ever since. No doubt this is time-consuming work. It perhaps may not be the most time-consuming among botanical dyes – but still time-intensive.

Image courtesy: BUAISOU; Photo: Nishimoto Kyoko

When the colour finally emerges, it’s just right. The labour involved in the production seems fitting and appropriate to me. At the end of it, it’s just a colour. It’s so pure, and therefore so simple. Whether it’s work or a work of art, ultimately it is a colour, and born out of a colour. That for me, is the beauty of indigo.

Image courtesy: BUAISOU; Photo: Nishimoto Kyoko

Image courtesy: BUAISOU; Photo: Nishimoto Kyoko

What is your favourite memory about indigo?

KK: After graduating from university, I worked part-time in an indigo dyeing workshop. Unfortunately, I did not get to work with indigo that much, and never really in depth.

The first year moving to Tokushima when we were able to dye with the indigo we made with our own hands was the most emotional and moving, and surprisingly recent, moment in my journey.

Image courtesy: BUAISOU; Photo: Nishimoto Kyoko

Image courtesy: BUAISOU; Photo: Nishimoto Kyoko

Often regarded as one of the oldest plant dyes for textiles1, indigo has been cultivated and used by humankind for thousands of years. Found in indigo plants, the pigment is extracted, fermented, reduced and oxidised in the dyeing process to colour textiles in the brilliant hues of indigo blue.

Image courtesy: BUAISOU; Photo: Nishimoto Kyoko

Against the backdrop of industrialisation in the 19th century, production and consumption models changed, and the demand for indigo grew. In the late 1800s, chemist Adolf von Baeyer successfully mapped the chemical structure of indigo from coal tar for synthetic manufacture and mass production2. Since then, the industry has opted for the more readily available and efficient, though less environmentally friendly, synthetic indigo dye3.

Of course we cannot talk about indigo without mentioning denim, the sturdy twill fabric and workwear staple, which was revolutionised by popular culture throughout the 20th century to become the iconic style and global phenomenon we know today.

Image courtesy: BUAISOU; Photo: Nishimoto Kyoko

The origins of the textile remain heavily contested. Denim is said to have originated in Nimes, France and also Genoa, Italy, before being brought to the United States just in time to meet the Gold Rush of the 1850s. Later research suggests that denim could even well have been an English textile, branded with a French name to appeal to consumer taste4.

Stepping beyond its muddled past, the textile, and perhaps the more familiar five-pocket, riveted denim jeans we know and love today, traversed the 20th century and transformed from its modest beginnings to become a symbol of industriousness and the romance of the American West in the 1930s, national identity and war effort during the Second World War in the early 1940s, to the bohemian and hippies culture of the 1960-70s. Later it evolved to embody various social movements and subcultures, before making its way to high-fashion runways in the late 1970s and onwards5.

Anything else you would like us to know?

KK: There is indeed a difference between synthetic indigo and natural indigo, and how they are used. When I first began making natural indigo, I had this disdain towards synthetic indigo. But after all, synthetic indigo could not have been made without natural indigo. The more I read into the history, the more interesting and meaningful it became.

I first became fascinated with jeans. Jeans, workwear, all of which are intertwined with war and military. The narratives of natural and synthetic indigo are interesting and carry tremendous significance. I hope we can keep in mind that both natural indigo and synthetic indigo dye are important.

Absolute Blue: BUAISOU Works with Japanese Natural Indigo is exhibited at CHAT until 5 February, 2023.

Reference

1 Kawahito, M., Awa natural indigo, NPO Awa Nouson Butai no Kai, 2015.

2 https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1905/baeyer/facts/

3 Douglas L., Kerstin N., Indigo: Cultivate, dye, create, Pavilion Books, 2018.

4 McClendon, E., Denim: Fashion’s Frontier, Yale University Press and The Fashion Insitute of Technology, 2016.

5 Fashionary, The Denim Manual: A Complete Visual Guide for the Denim Industry, Fashionary International, 2022

[wpsr_button id="1658"]